By Jennifer Levin

Images: C. Stanley Photography

Dr. Martin Luther King checks into a motel during a spring rainstorm. Weary after speaking at a local church, he takes off his shoes and relaxes on the bed, wishing for a cigarette. He begs the front desk for a hot cup of coffee. Sooner than he expects, a room-service maid arrives at his door. They banter. She’s witty and disarmingly bold, calling him “Preacher King.”

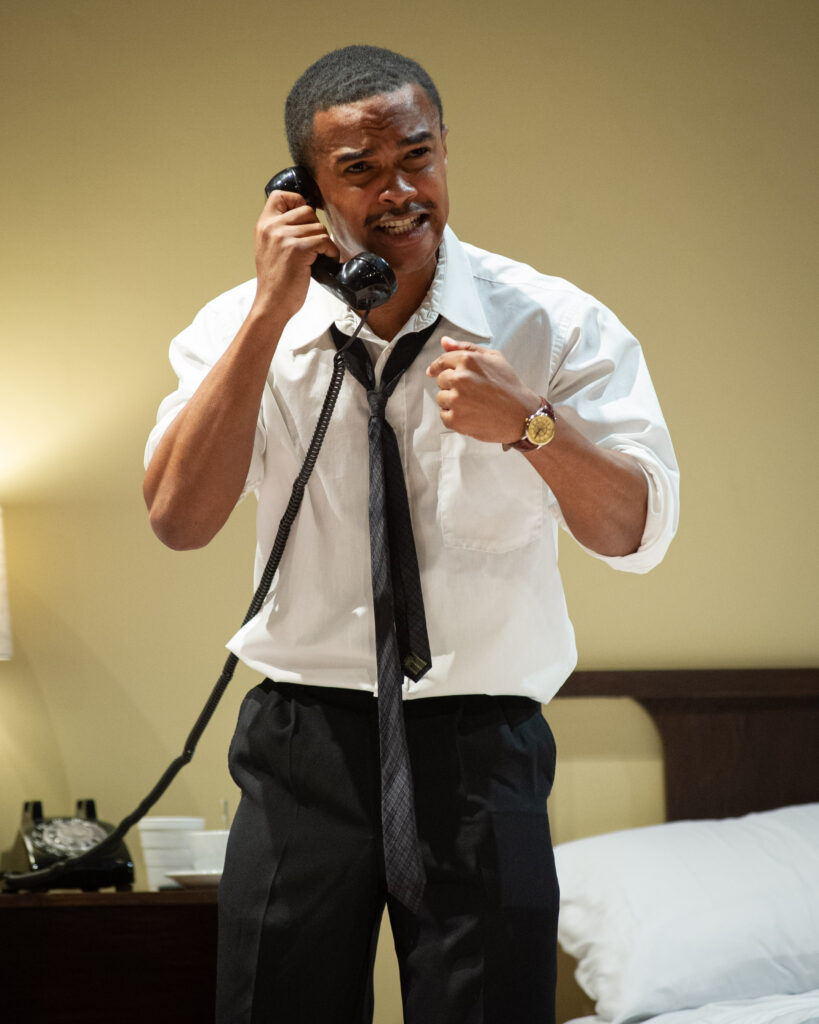

It’s April 3, 1968, and Preacher King has less than 24 hours left on Earth. What happens in his room at the Lorraine Motel that evening is the subject of The Mountaintop, written by Katori Hall, opening at the Santa Fe Playhouse on Saturday, Sept. 24. The production is directed by Zuhairah McGill and stars Langston Reese as Dr. King and Catia as the maid, Camae.

“There are sensuous, playful, intimate moments. They play these cat-and-mouse games with each other, and the audience sees them flirting,” McGill says. “Sometimes it looks like something, but it’s not what you think it is.”

Camae and King’s rapport deepens as the play unfolds. Something is afoot, or amiss; an ominous pall hangs over the room. Because of the real-time historical context, the audience has more insight into what is coming than King does, but not nearly as much as Camae. To explain that much further would spoil the story’s surprises.

The Mountaintop premiered at London’s Theatre503 in 2009 after American theaters were unreceptive to the play, which Hall workshopped at the Juilliard School’s Lila Acheson Wallace playwriting program. It went on to win the prestigious Olivier Award for Best Play. The 2011 Broadway premiere at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre starred Samuel L. Jackson, in his Broadway debut, as King, and Angela Bassett as Camae. In 2013 and 2014, it was one of the most produced plays in the United States.

It’s a challenging play for actors and the audience, with abrupt tonal shifts and a voyage into the spiritual realm. To prepare for the role of Dr. King and learn his vocal cadences, Reese listened to the civil rights leader’s speeches almost non-stop—as he fell asleep, as he got ready for the day, and during meals. As a Black man in his mid-20s, he’s had to learn about a period of American history that he didn’t live through but feels the impact of every day. However, the play isn’t about King’s stunning oratorial skills. It’s about his self-doubt in a quiet moment, when he’s feeling the weight of the world’s expectations, the yoke of governmental suspicion, the grinding persistence of racial animus, and fear over very real threats against his life.

“No one can be Martin Luther King. So, you do your best to show the humanity in him—and that starts with my humanity, seeing where I have my faults and shortcomings, and also my benefits and things that make me who I am,” Reese says. “I guess [my process] is a synthesis of understanding who he was, and also understanding who I am, and trying to blend them together.”

Catia, who is also in her mid-20s, is from Rhode Island. She has had to perfect a southern accent, but says she tends to pick up new speech patterns if she’s around them long enough. “Langston thought I could really be from the South, which I thought was ridiculous,” she laughed during a recent rehearsal, with a complete lack of the drawl she’d had only moments earlier. Her take on Camae is a high-energy, cold bucket of water—if not a potential warm bosom—for King. She enthusiastically lets him know what he doesn’t know, sometimes in black and white and sometimes more obliquely.

“I read this play at the start of the pandemic, to pass the time, and I thought it was one of the most beautiful scripts I’d ever read,” she says. “It immediately became a dream role of mine. Camae is a delight. She’s like the best version of myself, I could hope. It’s a joy to play her and it’s a challenge. I’ve never been challenged like this before.”

Although King was known to be supported by a cadre of strong Black women civil rights activists, many of whom didn’t get the credit they deserved at the time, McGill doesn’t see a modern feminist subtext to Camae’s character. “She isn’t coming from a feminist point of view. I think her point of view is of a Black woman, living in the ‘hood, who is poor, living paycheck to paycheck, taking care of herself. She’s had horrible things happen to her, by men,” McGill says. “But she stands up for what she believes. She comes in this room and she challenges Martin Luther King with her intelligence, using big words. She asks if he thinks poor people can’t talk like this.”

Although she was born after King died, Hall heard stories from her mother, who kept his photograph next to a picture of Jesus. McGill’s household also had pictures of King and Jesus, as well as Malcolm X. When she was a little girl, her mother took her to see Malcolm X speak, and her father took her to see Dr. King, whom she watched from atop his shoulders. Her parents’ activism set the stage for her own: the Philadelphia-based theater artist is the founder of First World Theater Ensemble, an African American company dedicated to plays about social issues. She says The Mountaintop is on her “bucket list” of plays she wants to direct, and feels dutybound to shepherd these young actors through this critical period piece.

“It’s my job to make sure they understand the pain, the agony, the weight, the dignity, the pride and the honor of 1968. And they have done a tremendous job. I’m very proud of both of them.”

Writing about the Broadway premiere, New York Times critic Ben Brantley equated the spiritual thrust of the play with sentiments he’s heard in Hallmark cards, whereas Variety’s Marylin Stasio had a more nuanced take, calling it a “deceptively trite situation that Hall transforms into an emotionally powerful and theatrically stunning moment of truth.” Unremarked upon in any of the major reviews is the play’s structural similarities to the speech that provides its title, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.”

King was speaking about the plight of the Memphis sanitation workers, who were striking for better working and employment conditions. In the speech, he restated his commitment to non-violence in the face of ongoing injustice, and the importance of not allowing the violence of others beat him down. He calls upon his listeners to rise up, to show unity, and for the preachers among them to remember that the immediate needs of the hungry outweigh any promise of future salvation. He also time-travels through history, visiting important, culture-shifting moments, including the one he’s in.

At the close of his speech, it’s almost as if King knew that death was coming for him. “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life,” he said. “Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!”

Performances of The Mountaintop run through Oct. 16. Get tickets.

Categorised in: News, The Mountaintop