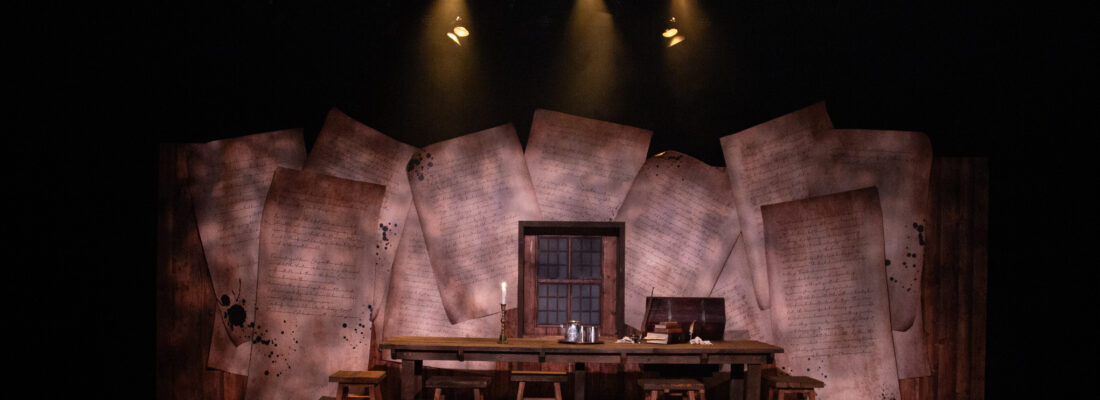

What is written on the Or, & Born With Teeth scenic parchment?

Directors Zoe Burke (Or,) and Antonio Miniño (Born With Teeth) did a lot of reading in preparation for their shows; in collaboration with scenic designer James W. Johnson, they decided to use text from the biographical materials they read instead of writings from Aphra Behn, Kit Marlowe, and William Shakespeare. The texts on the parchment were taken from the below excerpts. We hope to see you at Or, and Born With Teeth, performing through March 31, 2024.

Now post-Restoration, post-Victorian and postmodern, we should be able to cope with Aphra Behn, for, although secretive, she has many advantages for her reader. She thought a good deal about images of women and the strategies they used to find their way through life. Her historical moment, buttressed by her own temperament, situated her in a place between two patriarchal concepts of woman, one biblical, the other secular. Behn was curiously, although not completely, free from the first, while her antipathy to the second fuelled many of her imitated generalizations about women; opposing both, she asserted female desires and appetites when the prevailing culture taught that God had ordained women to delegate most of these. She also thought about writing and the relation of writing to the self and to the state which was Its context. Sexual politics was certainly her subject, but so was sexy politics and political Sex.

Despite her political expeditions and observations, Aphra had much time on her hands while in Surinam, and she used it in writing. Apart from the joy of creation, she was considering literature as a possible source of income in the future when espionage failed. It was a strange idea since no previous woman had been known to make a career in such a way, but these were new times and something might be made of the role. Inevitably as she looked at the real world through romance, so she created a fantasy one in its style.

In character she was gregarious, enjoying an evening of sociality; with the practiced female ability to work and converse simultaneously, she was rarely alone. She liked a drink, aware that it made one both witty and susceptible to wit in others. Probably amorous, she was sensual as much as sexual, interested both in men and women and appreciating beauty in both.

The actor in Shakespeare would have perceived what was powerful in Alleyn’s interpretation of Tamburlaine, but the poet in him understood something else: the magic that was drawing audiences did not reside entirely in the actor’s fine voice, nor even in the hero’s daring vision of the blissful object at which he lunges, the earthy crown. The hushed crowd was already tasting Tamburlaine’s power in the unprecedented energy and commanding eloquence of the play’s blank verse—the dynamic flow of unrhymed five-stress, ten-syllable lines—that the author, Christopher Marlowe, had mastered for the stage. This verse, like the dream of what ordinary speech would be like, were human beings something greater than they are, was by no means only bombast and bragging. Its appeal lay on its own “wondrous architecture”: its subtle rhythms, the way in which a succession of monosyllables suddenly flowers into the word “aspiring,” the pleasure of hearing “fruit” become “fruition.”

Shakespeare had never heard anything like this before. He must have said to himself something like, “You are not in Stratford anymore.”

This was a crucial experience for Shakespeare, a challenge to all of his aesthetic and moral and professional assumptions. The challenge must have been intensified when he learned that Marlowe was in effect his double: born in the same year, 1564, in a provincial town; the son not of a wealthy gentleman but of a common artisan, a shoemaker. Had Marlowe not existed, Shakespeare would no doubt have written plays, but those plays would have been decisively different. As it is, he gives the impression that he made the key move in his career—the decision not to make his living as an actor alone but to try also to write for the stage on which he performed—under Marlowe’s influence. The fingerprints of Tamburlaine are all over the plays that are among Shakespeare’s earliest known ventures as a playwright, the three parts of Henry VI—so much so that earlier textual scholars thought that the Henry VI plays must have been collaborative enterprises undertaken with Marlowe himself.

By 1589 or 1590 at the latest, Shakespeare reached Shoreditch and remained there during some of his apprentice days in the theatre. Marlowe, at this time, lived in the adjacent liberty of Norton Folgate, just north of the capital’s walls.

Few meetings between Elizabethan poets are on record, but the theatre’s circles were tiny. Actors and poets nodded to each other in the lanes. Even in a tavern, however, there were invisible barriers—matters of rank, affiliation, status—which kept men apart. A good deal would have divided a common, Stratford-born player from a Cambridge-trained, elite writer. Probably, at first, Marlowe viewed Shakespeare with cool indifference.

When he came to London to try his hand at playwriting, Marlowe had already begun a move from the artisan class to which his father belonged to the status of a gentleman—he had his university degree in hand—but he was hardly following a conventional life course. His overt sexual interest in men made that course still less conventional, while his opinions—according to the report of the intelligence agent who was assigned to spy on him and the testimony of his roommate Kyd–pushed him to the most dangerous frontiers of freethinking. He used to declare (or so thy spy claimed) that Jesus was a bastard and his mother a whore; that Moses was a “juggler,” that is, a trickster, who had deceived the Jews; that the existence of the American Indians disproved Old Testament chronology; that the New Testament was “filthily written” and that he, Marlowe, could do better; that Jesus and St. John were homosexual lovers; and so on.

Sooner or later, Marlowe became curious about the man from Stratford. What was there to learn about him?

Did they meet often? Or become intimate? Plainly, no record of their talk together survives. No obscure diary tells us of their meetings, though shreds of the truth can be discovered if we are willing to be patient, indirect, or somewhat roundabout in assessing Marlowe’s friendship with his prime contemporary. In this very small theatrical community, Shakespeare and Marlowe saw each other dozens of times, in an evolving relationship between 1590 and 1593, though the fact that no camera, no pen, no talkative host of the ‘Four Swans’ records their exchanges, is daunting.

——-

Sources:

Aphra Behn: A Secret Life by Janet Todd

Christopher Marlowe, Poet & Spy by Park Honan

Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, by Stephen Greenblatt

Don’t miss Or, and Born With Teeth! To learn more, visit santafeplayhouse.org/events/or-born-with-teeth/

Categorised in: News